A Boom Year For Law Schools, But What About Students, Legal Consumers, And Society?

May 2021

By

Mark A. Cohen

This article was originally published on Forbes.com and is reposted here with permission from Mark Cohen.

The world is one year into a pandemic that has radically altered our present and accelerated our future. Tom Friedman presciently opined in the early days of the scourge that Covid-19 would be an historical dividing line separating “ before-Corona (BC) and after-Corona (AC).”

A dramatic increase in law school applicants is one of many unanticipated consequences of 2020. This is great news for the Academy, but what about students, providers, consumers, and society?

Is the applicant surge market endorsement of law schools’ superior performance, product, delivery, value, innovation, transparency, market integration, and positive customer experience? Or is it lack of transparency perpetuating the widespread, false assumption that a law degree remains the ticket to a secure, predictable, highly-compensated career?

The surge explained by law school “experts”

The Law School Admission Council (LSAC) released statistics revealing a 35% increase in applicants and a 56% rise in total applications over last year. A recent U.S. News & World Report article on the law school applicant surge encouraged candidates “not to panic over the dramatic spike in applications and applicants.” It quoted tips from law school testing and admissions officers that included: test early, test often, apply early, and apply to several schools including less-competitive ones due to intense competition.

The “experts” offered a range of explanations for the applicant rise that ranged from “soul searching during quarantine….and the fragility of life;” to “more free time than usual during the pandemic….to fill out law school applications.” One law school administrator cited “certain current events that have raised the prominence of the legal profession…including the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the Black Lives Matter protests.” He noted a surge of idealism and the desire to right injustice as reasons for heightened interest in law schools.

The LSAT played an active role recruiting applicants. It specifically targeted candidates from lower-income households by loosening once-rigid test-taking requirements (LSAT-Flex) and providing online access for testing. The efforts produced a marked increase in African American applicants as well as an across-the-board rise in diversity candidates.

Another take on the applicant surge: A lack of data, transparency, and industry perspective

On its face, the steps taken to broaden interest in law school by tapping into social responsibility, righting injustice, and promoting diversity are commendable, if not long-overdue. But that’s just part of the story.

Most law school applicants lack essential data and industry perspective to make an informed decision about pursuing law school. The list includes: (1) data on cost, debt burden, job placement, and other key financial considerations; (2) accelerating legal industry changes and their absence in law school curricula and exposure; and (3) digital transformation and its impact on the legal function.

The law school applicant surge and the aggressive efforts to stoke it are reminiscent of the sub-prime mortgage crisis. That socio-economic imbroglio involved another salutary social objective: home ownership. It was a boon to mortgage brokers but financially and emotionally ruinous for many applicants whose interests the product purportedly sought to advance. Lack of transparency and predatory sales practices were the root cause of the debacle.

Law school by the numbers

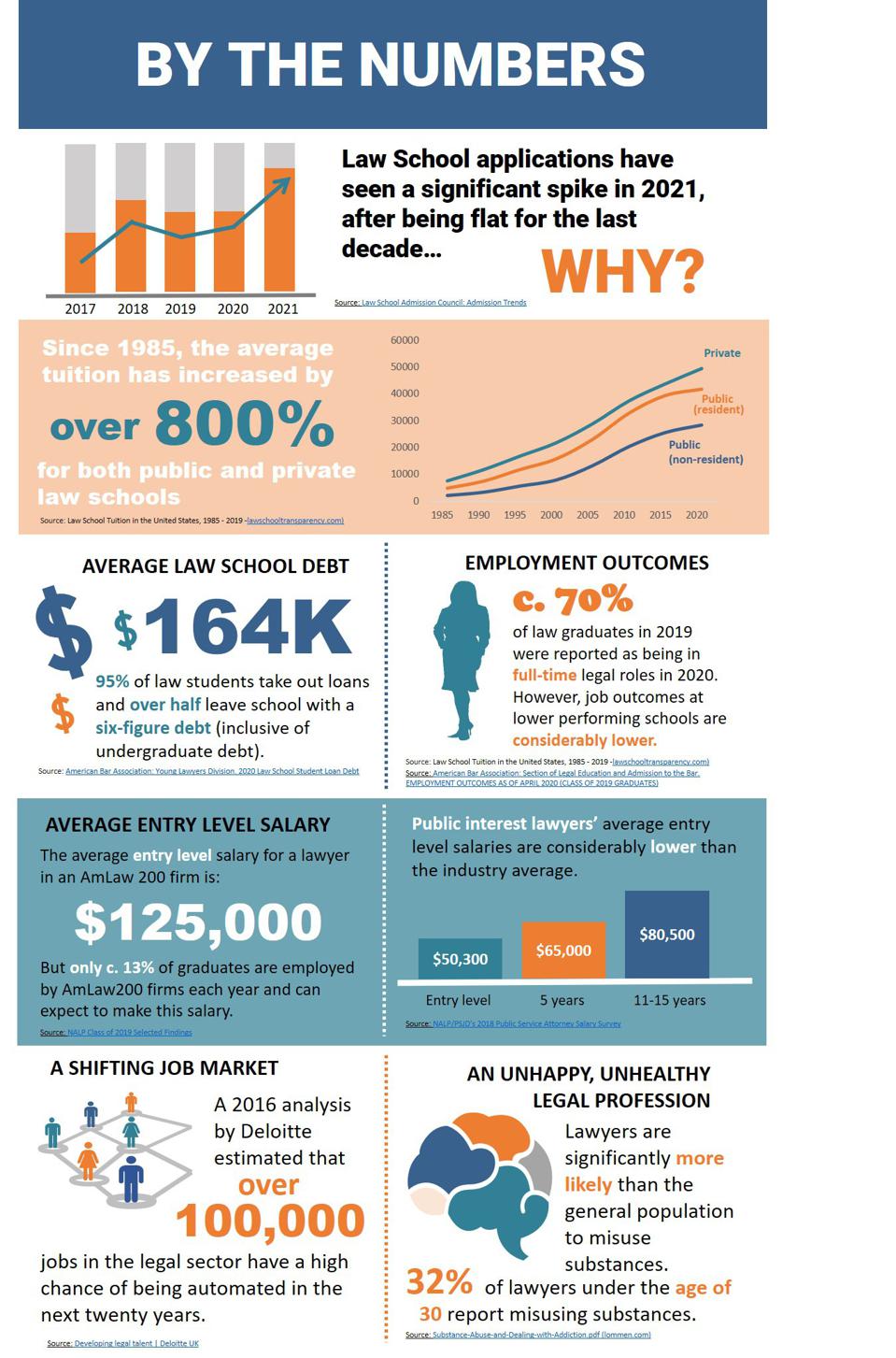

As a baseline, prospective applicants should be provided composite and individual law school data. Law school is an enormous financial commitment whose return on investment is unevenly distributed. The value of different law school brands; an applicant’s aptitude, skills, and financial circumstances; and a wide range of “non-practice,” business of law careers that do not require a law degree or licensure are key variables in prospective applicant’s cost-benefit analysis. The infographic below provides a snapshot of the law school landscape from the student perspective.

Highlights include:

- The average law school debt is $164K, and 95% of law students take out loans.

- Over half graduate with six-figure debt, and 40% see it expand five years after graduating.

- Only 70% of 2019 law grads were in broadly-defined full-time legal roles in 2020.

- High-paying Big Law jobs are dominated by grads from a handful of elite law schools;

- Starting salaries of most law grads are considerably lower than the 13% landing Big Law jobs;

- According to NALP data, average law firm attrition is 37% within the first 3 years of practice and 77% within the first 5.

- Public service positions are increasingly competitive and average $50,100 upon entry and $65,000 after 5 years.

- Lawyers are an unhealthy, unhappy profession whose alcohol and substance abuse, suicide, depression, and divorce statistics are among the highest of all Department of Labor job categories.

What is it to “think like a lawyer” in the digital age?

Law schools train students “how to think like a lawyer.” That worked when law was all about lawyers and most law grads segued from law school to firms where they received client-subsidized on-the-job training. Legal knowledge was what lawyers sold, and they had a monopoly of its supply and dictated the terms and conditions of its delivery. “The practice of law” was whatever lawyers deemed it to be, and only they could engage in it. Law schools and firms grew, prospered, and saw little incentive to change.

Those dynamics have changed.

Legal delivery requires not only differentiated legal expertise but also business management, technology, process and project management, data mining and analytics, design, economic, talent management, cybersecurity, and other expertise. Thomas Barothy, Group Legal Chief Operating Officer at UBS calls this “cognitive diversity.”

Multidisciplinary talent is required for the efficient, effective delivery of legal products and services. When it is melded with differentiated legal expertise backed by technology and data, it can productize and automate many high-volume/low-value and routine “legal” tasks. At the same time, it can leverage and scale differentiated practice expertise. Standardization and customization are both necessary to satisfy the needs of increasingly complex, dynamic, and customer-centric digital business.

Thinking like a lawyer in the digital age means focusing on the end-users of legal products and services. It means focusing on customers, using data and providing data-backed recommendations, and solving problems—not simply identifying issues. Thinking like a lawyer means working collaboratively and agilely to advance customer objectives, create value, and elevate the customer experience. It also means speaking the language of business, communicating in plain-speak, working at the speed of business, not law, and recognizing that legal products and services are a means to an end—solving customer challenges—not simply “producing the best legal work product possible.”

Law schools are not preparing students to think like a customer-centric lawyer. Nor are they providing them with contemporary skills required to augment a rudimentary knowledge of doctrinal law. These additional skills include but are not limited to: the basics of business, technology applied to legal delivery, process and project management, data analytics, and digital transformation and its impact on the legal function.

Law schools are preparing students for vanishing careers

Law schools continue to prepare grads for practice careers that are vanishing. Legal practice is shrinking because of artificial intelligence, automation, disaggregation, and an array of other powerful macro-economic trends that are transforming multiple industries—law included. For most lawyers in the digital age, law will be a skill, not practice.

A 2016 Deloitte study projected that in excess of 100,00 legal jobs could be automated by the end of this decade, and the acceleration of digital transformation created by Covid-19 will likely increase that total. Those redundancies will be offset by new jobs that require fresh skills, agility, and a commitment to up-skilling. The problem is that law schools are not anticipating—much less preparing— students for the challenges and opportunities of the digital age.

Law school is no longer the only game in town, especially for those keen to pursue a legal career that does not involve the practice of law. Other lower-cost professional schools, online skills-based courses, self-help tools, and experiential learning opportunities exist that do not require a law degree.

Digital transformation and the legal function

Law’s future is its customers’ present. Digital transformation is an essential element of that present—an existential and competitive imperative. The extension of digital to the legal function will be a seminal force in reshaping its role, remit, and standing with its clients/customers and their customers.

Digital transformation begins and ends with customers, the North Star of business. The objective of business is to provide customers with a positive, pleasing, productive, and personalized end-to-end experience. Technology is the digital journey’s engine, and data is its fuel. They are the principal tools that enable business to reimagine the customer experience from the customer perspective.

Digital transformation also involves people—the organizational culture and values they create, their structure, processes, supply chains, collaboration, talent management, skills and up-skilling required to keep pace with technology and data to elevate the customer experience, and change management. Digital transformation has been a C-Suite priority for years; Covid-19 has accelerated the pace of digital change and separated digital leaders from laggards.

Digital is a team sport. Individuals, teams, the entire supply chain— including strategic partners, business units, and the enterprise—all engage to advance customer outcomes and elevate experience. There are no hall passes, and that includes legal. The legal function is a digital laggard, but that will soon change. The C-Suite expects the legal function to operate like other business units. That means it must be proactive, agile, cognitively diverse, collaborative, data-driven, holistic, innovative, create value, mitigate risk and customer-centric.

Conclusion

This is the exposure and training law applicants should expect—but will not receive—at law school. A dollop of “innovation,” “legal entrepreneurship,” and other curriculum clickbait courses do not begin to address the urgent need for digital preparedness and training of law students and the wider legal ecosystem.

What’s required is a re-imagination of legal education and career-long training designed from the end-user-of-legal-services perspective.

The pandemic-produced spike in law school applicants may well be a sucker’s rally and a painful lesson in caveat emptor.

Posted by

Mark A. Cohen

Related Content

Portrait Of The Customer-Centric Legal Function

Mark A. Cohen discusses how the digital transformation necessitates a focus on customers and how it is a paradigm-shifting journey that must include legal.

How Does The Legal Function Demonstrate Value To Business?

Mark A. Cohen examines why the legal function has difficulty proving its value to business and proffers how it can make its case.

Law is a Team Sport in the Digital Age

Mark Cohen discusses how legal teams must be truly multidisciplinary in order to work cross-functionally to solve complex business challenges and seize opportunities.

- Expertise

- North America

- Legal Department Management

- Must Read

- Perspectives

- Work and Career

- State of the Legal Industry

- Legal Technology

- Spotlight

- Solutions

- Artificial Intelligence

- Regulatory & Compliance

- United Kingdom

- Data Privacy & Cybersecurity

- General Counsel

- Legal Operations

- Australia

- Central Europe

- Commercial & Contract Law

- DGC Report

- Labor & Employment

- Regulatory Response

- Technology

- Banking

- Commercial Transaction

- Diversified Financial Services

- Hong Kong

- Intellectual Property

- Investment Banking

- Large Projects

- News

- Singapore